Jacob Aagaard is an author whose non-opening books I almost always (or maybe just always) buy. It isn't his writing style, which is a bit too sarcastic for my taste, but because of his professionalism. His books represent honest labor: he has put real effort into selecting the material and properly analyzing it. Further, while it is certainly possible to disagree with his ideas, he has a well worked-out theory of chess, too, so one gets both the forest and the trees from his works.

His most recent work is Positional Play, the second of five books in his "Grandmaster Preparation" series. The book is built around a very simple approach, which is that "all you need are three questions":

1. Where are the weaknesses?

2. Which is the worst-placed piece?

3. What is your opponent's idea?

Aagaard makes clear that by saying that this is "all you need" he doesn't mean that reflecting on these three questions will enable one to play perfect positional chess. Remember that this is the "Grandmaster Preparation" series, and his target audience will already play at a pretty high level and possess a good deal of acumen when it comes to positional understanding. Aagaard's goal is "not [primarily] to make you understand chess better," but rather "to teach positional judgment and decision-making." As he also says, "[t]he purpose of the three questions is to direct your focus".

This is a useful aim, and it seems to me that the first and third questions are especially valuable and usable for players of almost any level. The second question, which I've heard attributed to Makagonov and others, seems a bit more iffy to me, both in terms of use and definition, though there are certainly times when focusing on that question can be of use.

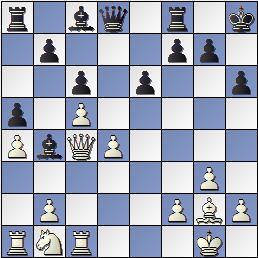

At any rate, the book has gotten off to a slightly bumpy start for me. The book's second example, in a proto-chapter called "Visualizing the Three Questions", starts with this position (with Black to move) from Giri-Aronian, from last year's Olympiad in Istanbul:

Aagaard highlights White's d-pawn as a weakness and c5 and b2 as potential weaknesses (question 1); considers the white knight on b1 and the black bishop on c8 as the worst-placed pieces for each side (question 2), and highlights Nb1-c3-e4-d6 as White's plan (question 3).

Before going on with the game, a question (or two): why is the white knight his worst-placed piece? Of course it isn't great on b1, but it has a future and can immediately find a decent home on c3, with e4 and d6 being even better. Why isn't the rook on a1 the worst-placed piece? It's really stupid on a1, and while nothing prevents the knight from hopping into the action, the rook on a1 is hemmed in by the knight and the other rook too. Unless we define "worst-placed" by a sort of subtraction (value of the best square it can reasonably head for minus the value of the square it's currently on), it's hard to see how the knight is really the best candidate here.

Let's move on. Aronian played 18...e5!, to which my first inclination was "what?" It's not that I don't see the point of the move - of course I do. Further, the more one looks at it, the more obvious it is that it's the correct move. Black's bishop is liberated and the c5 pawn is weakened. My surprise isn't really the move but in seeing how it's supposed to emerge from reflection on The Three Questions. On the plus side, it takes care of Black's worst-placed piece and renders c5 a more serious weakness. (The b-pawn is also rendered a touch weaker.) But the pawn that was listed as THE weakness is not only being assailed, but is allowed to purchase its own value in advance!

Indeed, I even wonder a little about Aagaard's labeling the c5 pawn as a potential weakness in his initial inventory. One might not suspect such a thing until and unless ...e5 sprang into one's mind. This seems like the sort of ex post facto justification criticized by authors like Willy Hendriks in Move First, Think Later. (For a bit about the book, have a look at John Watson's review thereof.)

For a real horror, imagine trying to apply Aagaard's Three Questions from the start of the game. "What are the weaknesses? Well, f2 and f7, obviously - they're only protected once, and that by the king. What are the worst placed pieces? That's easy - the queen's rooks. What is Black's plan? Well, being a rational individual, he's probably thinking the same way I am, and he'll either go for my f2 or improve his worst-placed piece. So I know! I'll go for f7, improve my worst-placed piece and prevent his plan with 1.a4!!"

Well done! Now it's Black's turn. "Okay, my opponent has played 1.a4 - clearly he wants to activate the rook and go for f7. Can I stop this? Yes, I'll play 1...e6! That prevents Ra3, while also shielding f7 from a bishop or queen on the a2-g8 diagonal. It's true that it doesn't do anything for my worst-placed piece, but if 1...a5 2.Ra3 Ra6 3.Rf3 Rf6 4.b3! followed by 5.Bb2 forces the exchange on f3, and then I'm helping him develop. So I'll stick to 1...e6."

White again: "Yes, that's very clever. He is ready to develop some pieces, and he has pervented Ra3-Rf3. But I have two rooks, and my rook on h1 is only slightly worse-placed than the other rook. So now I'll play 2.h4, followed by Rh3, h5 (if the h-pawn is still eyed by his queen) and Rf3. Problem solved!"

Ridiculous, I know. The answer Aagaard might give is that he isn't offering a method in the way that Nimzowitsch's My System or Jeremy Silman's How to Reassess Your Chess does. His book tries to show a player what to focus on, that's all. But that doesn't really seem to be a satisfying answer. It isn't hard to think of positions where The Three Questions are useless, and not just on move 1. So how do we focus our thinking then? Either we need more questions, or we need to turn The Three Questions into a proper method by learning how to apply them even in cases where they don't yet seem to be relevant.

A closing comment, which may or may not turn into a promissory note. While Hendriks makes some reasonable criticisms, I don't really agree with his anti-methodism. When we "see" what to do it doesn't at all mean that we've left the rules behind; rather, some principles are so integrated into our thinking patterns that when a position resembles our mental stereotypes closely enough we'll almost instantly understand what to do. Further, on those occasions when we don't know what to do, when our tacit knowledge doesn't immediately or quickly come to the rescue, then reflecting on questions of method - like The Three Questions - can help us. My worry that those questions aren't enough even for the limited aims Aagaard wants them for, but that doesn't mean that I don't find those questions - and the aims Aagaard has for them - altogether valuable.